The Bank of England is an institution that played a key role in the creation of the modern industrial world. Established in 1694, it has reinvented itself several times over the last 300 years. In many ways, its evolution as an organisation can be traced in the history of the buildings it has inhabited, starting in rented premises, moving through a period of rapid expansion and transformation, settling down in the 19th century to a long period of stability and reverence, only to undergo upheaval once again following the first world war.

Sir John Soane was the most famous and arguably the most complex of the bank’s architects and the bank has come to represent his genius like no other project. It forms the centrepiece of our story. Created over a 45 year period at a hinge point in world history. While Soane was transforming the bank’s premises, Britain was becoming the first country to transform it’s economy from animal power to fossil fuel based industrial production.

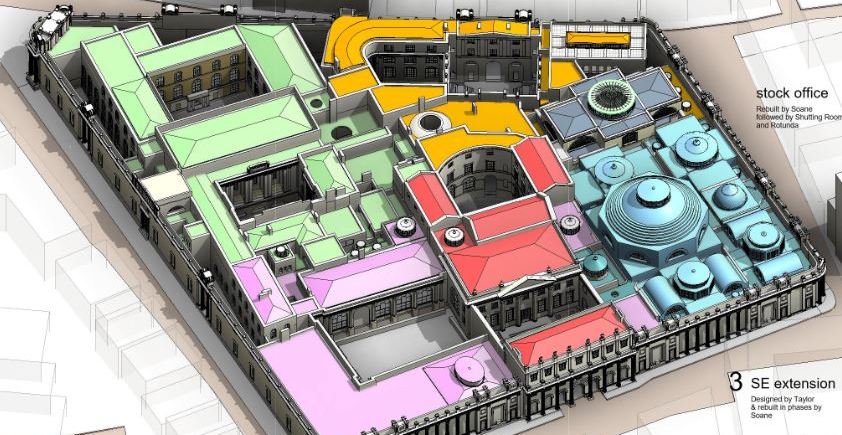

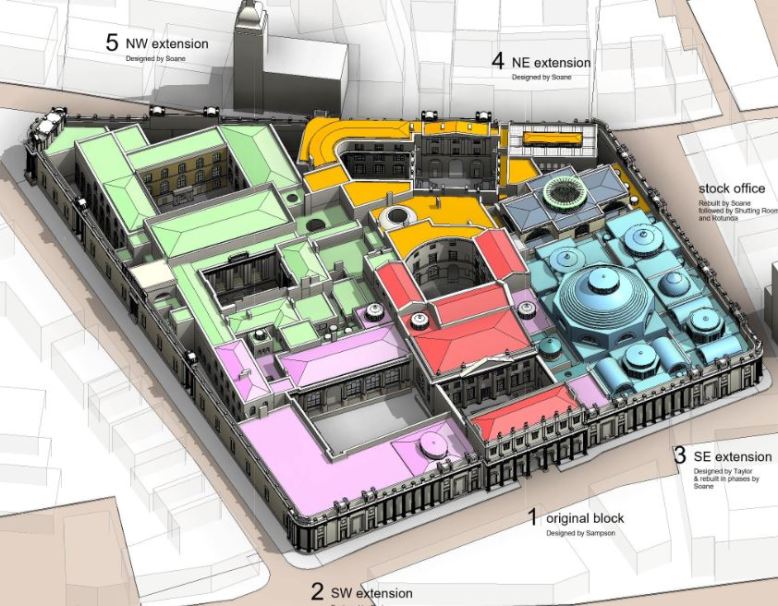

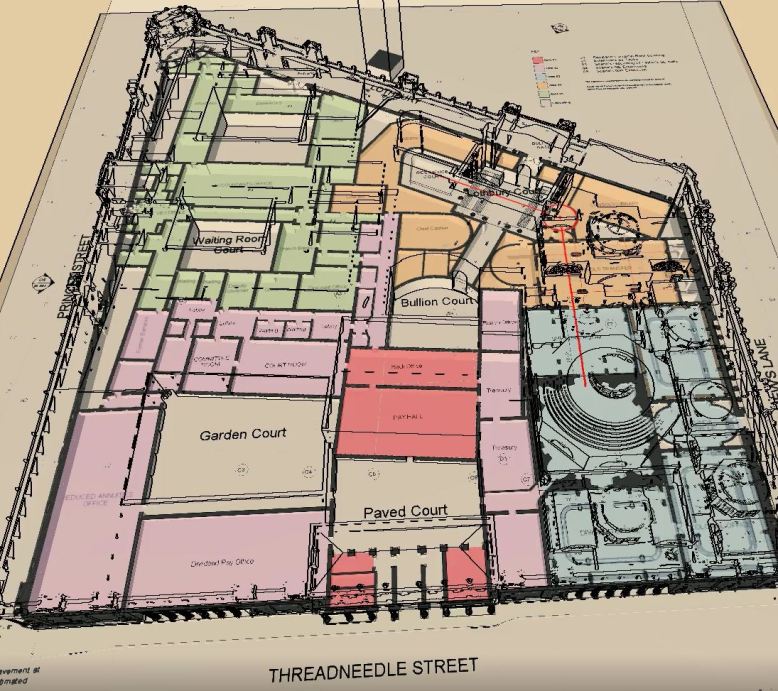

In 1833 when Soane retired, he left behind a complex structure that resembled a medieval walled city: an irregular jumble of buildings crammed within an outer defensive wall, complete with battlements and city gates. Indeed it could be seen as a microcosm of the City of London itself, from which it evolved. Inside the walls could be found traces of the work of two earlier architects, Sampson & Taylor, but Soane had spun a yarn of his own around these older stories, incorporating them into an epic romantic poem.

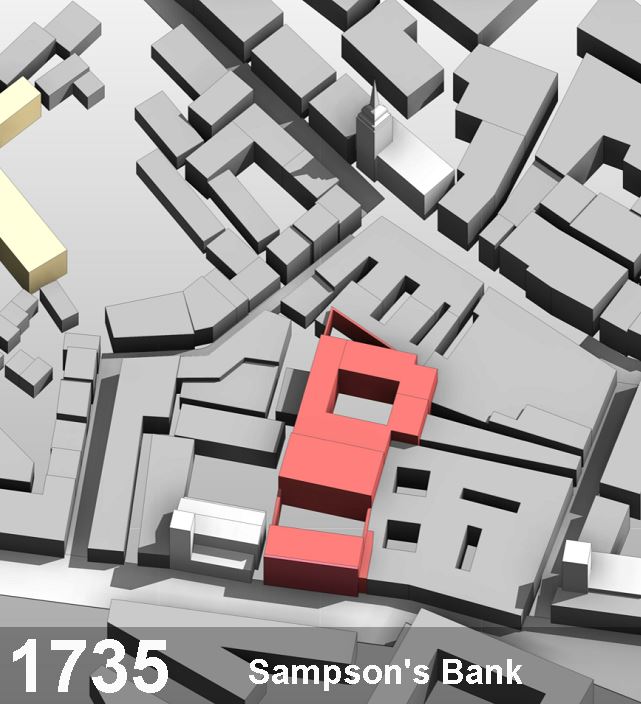

Sampson designed the Bank’s first purpose-made building, a double-courtyard block squeezed into a narrow plot in the middle of a congested city block, with a church on one side, houses, inns and workshops all around. This was a modest building, in the prevailing Palladian style of the times, placed discreetly into the existing streetscape.

Here was a bank that was making a huge impact on the financial affairs of the nation, underwriting national war debts, and guaranteeing private loans to the state with impeccable standards of book-keeping and confidentiality. There were many reasons for the much longer established goldsmith bankers to resent their intrusion and for the general public to mistrust their substitution of paper for gold. Hence the understated nature of Sampson’s scheme.

But business continued to boom, and the bank started to buy up adjacent properties with a view to expanding. By the time they appointed Sir Robert Taylor to design a new extension to the east, they were ready to project a much bolder image. Over the next couple of decades they expanded to both East and West, creating a grand palace front facing Threadneedle Street for a whole city block.

John Soane was a young, ambitious architect when he was appointed to take over after Taylor died. The directors were making an interesting move, swapping the swagger of the leading architect of the day for the measured, but innovative approach of a newcomer. Over the next 45 years, architect and client evolved in tandem, learning from each other as global commerce expanded at an astonishing rate, with the City of London at its centre.

Soane began with minor alterations and additions, plus surveys of the existing structure, eventually persuading the Bank to replace two of Taylor’s transfer halls, whose complex timber roofs were leaking badly. One of these, the Bank Stock Office, has been restored in modern times and now houses the Bank Museum: well worth a visit if you get the chance.

But the bank was still expanding and Soane was tasked with buying up more property behind the existing premises. This led to his North-East Extension which transformed the Bank into a self-contained entity, walled on all sides and separated by roads from all its neighbours.

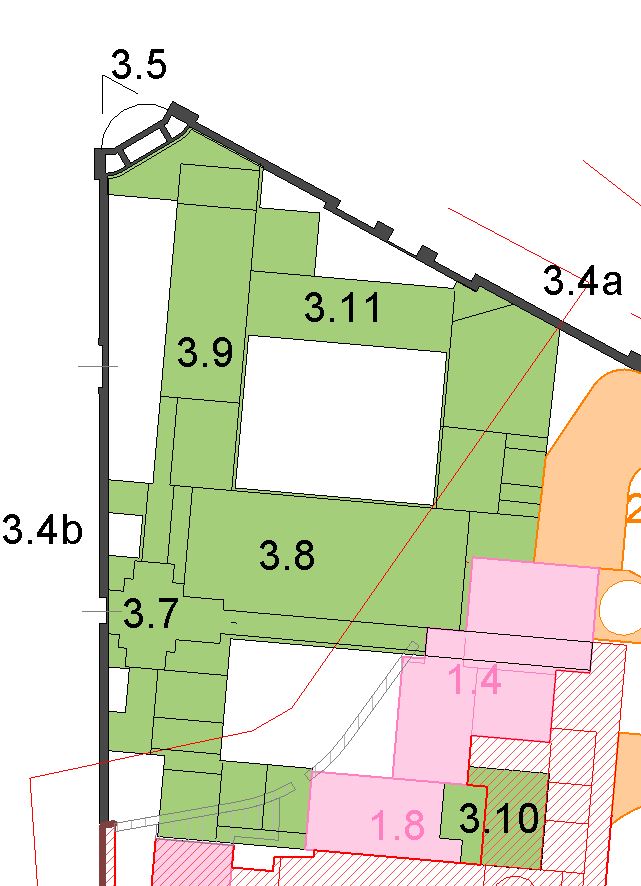

Already you can see a huge contrast with Taylor’s work. In place of the grand symmetry we know have a carefully studied solution to a complex planning problem. The exterior screen is muted in expression as Soane prefers to express the bank’s persona internally by way of Lothbury Court which celebrates the bullion route.

Somehow he manages to rescue symmetry and grandeur from the constraints of a narrow, irregular site with conflicting levels, housing a wide range of functions. (Library, Residences, Offices, Transfer Hall, Porters Lodge) Changes in angle are cleverly negotiated using semi-circular spaces as mediating pivots.

Apart from the technical skill involved in this planning exercise, Soane had to display considerable resolve in persuading the building committee to accept his solution. Taylor’s existing Library block had to be relocated, in order to create the elbow room he needed for the double-courtyard arrangement.

It is tempting to see a parallel between the relationship of Soane to his committee, and the checks and balances of political life in eighteenth century England. The Bank of England had stood its ground against the government on several occasions, insisting on its independent professional viewpoint as a financial institution representing commercial interest. Similarly Soane could be very stubborn in upholding his architectural convictions against penny-pinching accountants.

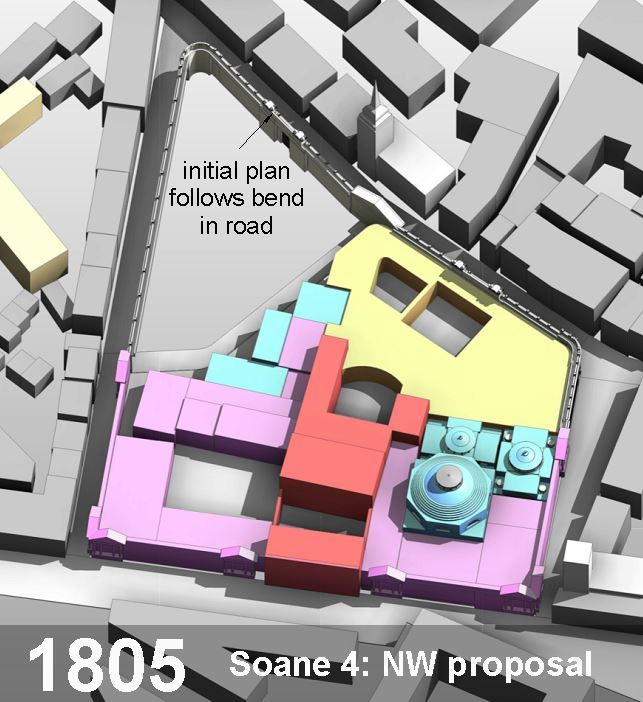

But no sooner had he resolved one complex planning puzzle, than another very different challenge appeared on the horizon. Staff levels continued to rise, and the directors were determined to expand to the North-West. Having cleverly woven the premises into a single, self-contained entity, Soane would have to break it open again, negotiate a road closure and diversion, outwit the powerful Company of Mercers and design a very different kind of extension within a triangular space.

Bank Notes had been around for a long time, longer than the Bank of England itself. But they had always been the preserve of the moneyed classes: large denominations suited to transactions between men of business. All that was about to change however. The North-West Extension was to house new printing and accounting facilities for lower denomination bills that could supplement the metal money in general circulation on the street. This was the beginning of the Bank Note as we know it today. There was to be suspicion and resistance, but ultimately a transformation of the economy comparable to the transitions to plastic money and digital payment systems that we have seen in modern times.

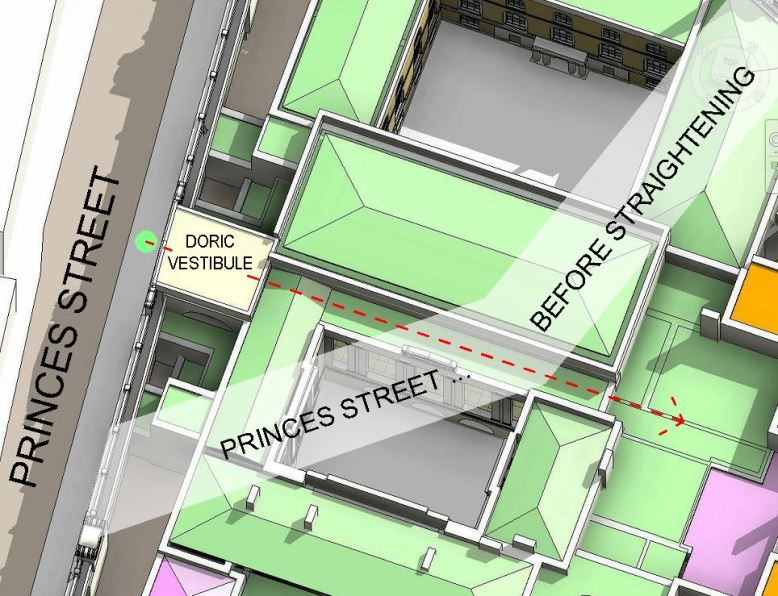

Soane investigated several approaches to the planning of this extension, but ultimately opted for the discipline of an orthogonal grid, based on the orientation of Sampson’s original Pay Hall, and the Bullion Court behind it. Wherever this grid intersected with the new boundaries (along Lothbury and Princes Street) he allowed narrow, wedge-shaped courts to take up the slack. This resulted in a deceptively simple, double-courtyard solution, reminiscent perhaps of Sampson’s original scheme.

But hidden within the clarity of this scheme were a number of subtle and complex manoeuvres. He was required to find a discreet alternative entrance to the Directors’ Parlours. Important clients were having to squeeze past the general public in the crowded Pay Hall to reach the Governor’s Office. Soane came up with a dramatic processional route, starting with a new Doric Vestibule, centrally placed along the new, straightened Princes Street façade.

Doric Vestibule, leading to the Long Passage

From there he created a long, L-shaped sequence of passages and lobbies, rising to the challenge of enlivening the route with effects of lighting and changes in scale, before turning back on itself to enter Taylor’s domed entrance lobby to the Court Suite. Along the way, this passage offered views into the newly created Waiting Room Court, and the much older Bullion Court, now suitably buried deep in the heart of the bank complex.

Waiting Room Court

At the North-West apex of the scheme Soane was faced with a 60 degree angle. He was never a man to grasp the first idea that came into his head, and drawings for several alternatives survive in the Soane Museum archive. The chosen solution survives today, though somewhat altered, and goes by the name of Tivoli Corner, after the circular Greek temple that was Soane’s inspiration. There are two versions of this temple in the model room at the museum, one in plaster showing it complete and pristine, the other in cork, as a ruin.

But perhaps the most challenging aspect of all was how to weave together old and new, splicing the new fabric into the back of the director’s parlours. This was just the kind of nuggetty challenge that Soane thrived on, and the result is a typically inventive and varied spatial sequence, employing just about every trick of top-lighting you could imagine. It begins with Taylor’s entrance lobby, passes through a low, narrow passage and into a central lobby with large semi-circular lights on either side of a steep, groin-vaulted ceiling, concluding with the Rustic Lobby, a space like the inside of a tower, lit from above by a series of narrow, round-headed windows.

In the space of 20 years, Soane had doubled the size of the Bank, solved a seemingly endless series of complex functional, structural and aesthetic puzzles with great panache, and generally tended to the needs of an institution undergoing a remarkable evolutionary process as it helped to shape the nature of new financial world order. British manufactures were beginning to dominate world trade and the Bank was becoming the touchstone of stability and integrity.

Soane himself had grown in stature although always a controversial figure, a workaholic, and acutely sensitive to criticism. He was also very wealthy, having inherited sizeable property holdings from his wife’s uncle, and had become an avid collector. His next 20 years as architect to the Bank would be less dramatic, but equally rigorous and rewarding, as he extended his touch to almost every part of the complex, aiming for a unity of feeling but a variety of spatial effects.

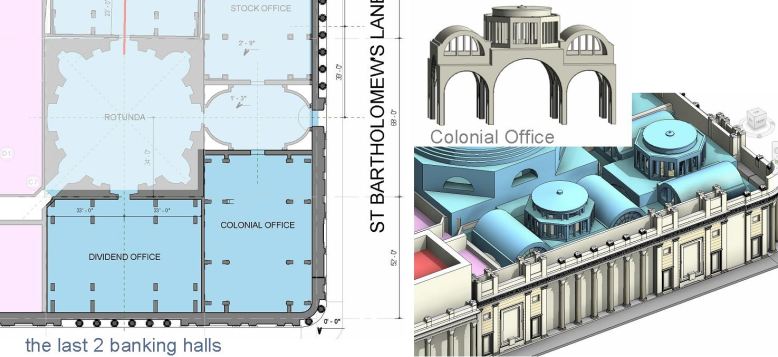

He finally got around to replacing Taylor’s last two transfer halls, continuing the theme that he had established in three previous attempts, but adding fresh interpretations, and in particular emphasising a continuous flow of arches and vaults.

Spaces such as the Bullion Vaults and the Treasury were refitted, and finally, after a long campaign he managed to persuade the directors to allow him to unify the external screen wall with a consistent treatment all around. Given the way that this wall had evolved from rather humble beginnings as a short length around the back of the site, his ability to pick up the threads after more than a decade and weave them into a convincing story is particularly impressive. Here is a wall that announces the stability of the bank, declares the identity of its designer and blends graciously into its context.

Furthermore, it is a wall that could adapt yet again a century later without losing its essential character. Some of us may feel that Herbert Baker could have retained more of the original parapet, mourn the loss of the Tivoli attic, but the fact remains that Soane’s conception had the strength to survive quite radical remodelling and still maintain its identity.

Threadneedle Street, re-faced by Soane

Which brings us to Baker. If Soane’s bank represents the beginning of Britain’s industrial revolution, and the age of empire, the first world war brought a rude awakening. The Bank began as a mechanism for financing European wars, and its activity had grown well beyond the capacity of the existing structure during the course of this new conflict. There only seemed to be one solution: to replace what was, on average a two storey structure, with a new building that went “up seven and down three”

Baker was an intelligent and sophisticated man at the height of his powers. In that sense the choice resembled the selection of Taylor 170 years earlier. Like Soane before him, he elected to stamp his own identity on the building, making references to the work of previous architects, but subsuming them into his own chosen style. In the end this seems to be inspired by none of them, but instead to hark back to the all-purpose classicism of Christopher Wren, with a bit of modern statuary thrown in for good measure.

It was a steel framed structure, built in two halves to allow for continuity of operation. Certainly it was a remarkable achievement, but it would be difficult to call it a great piece of architecture. To be frank, it’s rather pompous and there’s something rather odd about the proportions. All the same, it’s unlikely to be swept aside in the foreseeable future. Times have changed since Soane’s masterpiece was demolished.